The major fighting powers, with the exception of the United States had largely abandoned the idea of airships as weapons by the time the conflict ended. However, the part they played in observation flowed naturally into civilian life, for example advertising, sightseeing, surveillance, research and promotion.

Russia had completed its second airship in later 1944. This was a Probeda (Victory) Class used for clearing wrecks and mines in the Black Sea. It also commissioned the W-12bis Patriot in 1947, and deployed it through to the mid-1950’s for crew training, parades and public events.

Post War American Military Airships

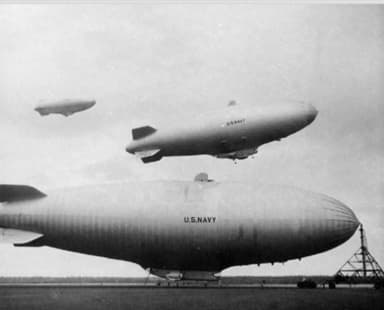

America was a notable exception to the policy of standing down military airships and blimps. That’s because they had proved useful as submarine hunters, convoy escorts, and search and rescue vessels during World War II.

As relationships with Russia cooled, America redeployed airships to a new mission. Airships would become unarmed airborne listening posts. They would patrol vast expanses of ocean off America’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts, watching and listening.

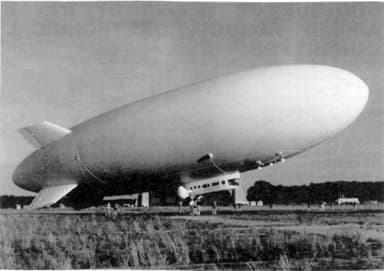

A new series of N-Class navy blimps emerged. Eighteen were configured for both anti-submarine warfare and airborne early warning missions, and were delivered between 1952 and 1957 with these specifications:

- Length 343 feet, diameter 76 feet, capacity 1,011,000 cu ft

- Propulsion 2 × Wright R-1300-4,-4A Cyclone 7 radials , 800 hp each

- Maximum speed 80 mph, endurance over 200 hours, crew 21

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N_class_blimp.jpg

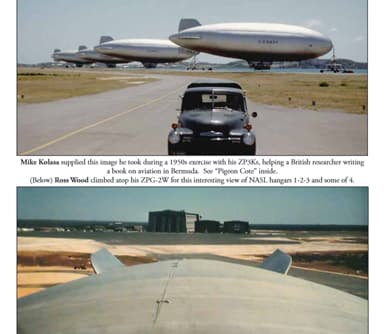

The U.S. Navy commissioned a new blimp type in 1957. This was designated ZPG-3W. This time the engines were moved to the outside of the vessel, and larger radar antennas were installed inside the 1,516,000-cubic-foot envelope.

http://www.issi-md.com/PDF/Naval_airships-newsletter_2010.pdf

Four of these ZPG-3W blimps were delivered to the Navy with the following specifications:

- Length 403 feet, diameter 85 feet, maximum speed 80 mph

- Power plant: Two,1,525 hp Wright Cyclone aero engines

https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/a-very-short-history-of-postwar-military-airships/

They began patrolling the ocean from Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst in December 1959. On July 6, 1960 one suffered a catastrophic envelope collapse off Long Beach Island, New Jersey killing 18 of 21 crew.

https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/systems/zpg-3.htm

The United States Navy began to cut back on its airship program as other airborne options came on stream. It commissioned its last two airships on October 31, 1960, and finally retired the two it kept at Lakehurst for research on August 31, 1962. But would this be the end of the era for U.S. lighter-than-air flight?

The Pre-Space Age Manhigh Project

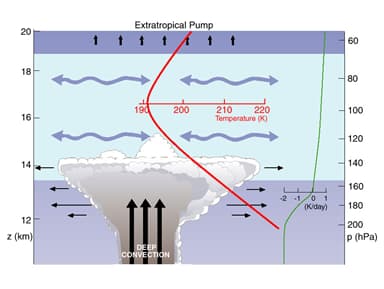

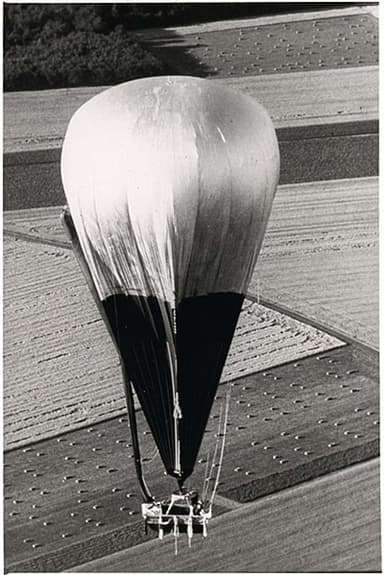

While the U.S. Navy was experimenting with airships, the U.S. Airforce had other things in mind. It launched Project Manhigh in 1955 as an aero-medical research program. This involved sending men in balloons to the middle layers of the stratosphere as a stepping stone to space itself.

https://atmos.uw.edu/academic/midatmos.html

Candidate balloonists wishing to participate in studies of the effects of cosmic rays on humans underwent a series of physical and psychological tests. These became the standard for qualifying astronauts for Project Mercury. That was America’s first manned space program lasting from 1955 to 1958.

Project Manhigh comprised three balloon flights into the stratosphere as follows:

- Manhigh 1 reached 96,784 feet with Captain Joseph W. Kittinger at the controls on June 2, 1957. The exercise was aborted when engineers discovered one of the capsule’s valves was installed backwards which vented the oxygen supply outside.

- Manhigh 2 took Major David G. Simons to an elevation of 101,516 feet during August 19 / 20, 1957. The pilot completed 25 experiments and observations. The balloon expanded to a 200-foot diameter, with a volume of 111,000 cubic yards.

- Manhigh III reached 98,097 feet on October 8, 1958 under control of Lieutenant Clifton M. McClure. There’s rich detail obtainable at this link. The capsule was 8 feet high and 3 feet diameter.

The capsule containing the rider hung from an open, 40,4 foot extended skirt parachute with six suspension fittings positioned circumferentially around the turret casing.

This parachute was in turn attached to the balloon by a stabilizing suspension system, to retard any capsule oscillations during the experiment.

http://stratocat.com.ar/fichas-e/1958/HMN-19581008.htm

The American Nuclear Powered Airship Program

The U.S. Navy Bureau of Aeronautics published a preliminary study into a nuclear-powered airship in April, 1954. This seemed a logical extension to the emerging nuclear age. The idea of airships flying for years without refueling would have distinct military advantages.

https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/358153.pdf

U.S. Government Work Taken to be in Public Domain

The authors of the report envisaged the following specification for the first nuclear-powered airship:

- Gross Weight 120,000 lb, military load 30,000 lb

- Crew 30, cruising speed 115 mph, cruising altitude 10,000 ft

- Volume of envelope 2,000,000 cu ft, power requirement 4,500 hp

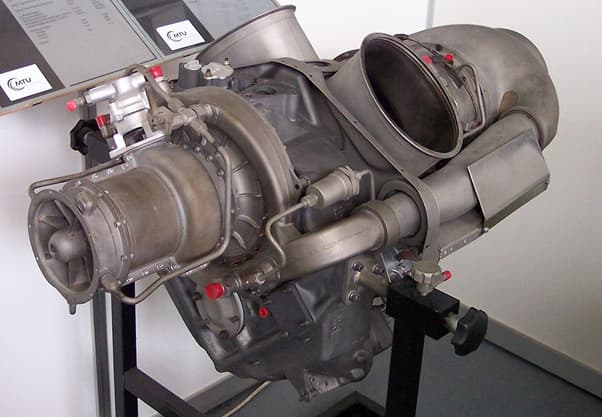

- Propulsion 2 T-56 gas turbines modified for nuclear propulsion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allison_Model_250#/media/File:Allison_(MTU)_250_C20B.jpg

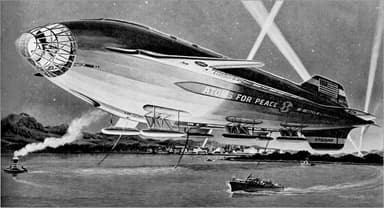

The authors recommended a rigid airship design, with the turbines and reactor positioned amidships for strength and stability. Crew facilities would be generous because of long flights. There was talk of using the entire forward section for crew exercising and recreation.

U.S. President Eisenhower was not convinced the idea was feasible. He redirected the project to launching the first nuclear power merchant ship NS Savannah in 1959. This foundered in the high costs of nuclear in 1971, as might have likely sunk the nuclear airship project had it continued.

Goodyear had several attempts to breathe new life into nuclear airships. They had the capability to do this. However, the military imagination had moved on, albeit not the mind of the public.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/dlberek/4981420966/in/photostream/

The Era of the Adventurous Balloonist

Governments around the world had abandoned interest in airships with the exception of the U.S. military. There had been too many accidents, and too many deaths for their stakeholders to stomach. The Hindenburg was simply the final coup de grace.

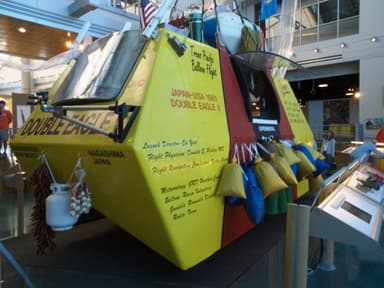

Only a few intrepid adventurers pressed on. However, they had to revert to balloons, for this was all they could afford without large defence budgets. On August 11, 1978 three Americans lifted off from Presque Isle, Maine on a mission to cross the Atlantic and land at Paris.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DoubleEagleIIPresqueIsleMaine.jpg

As an aside going back in time, their balloon, ‘Double Eagle II’ was the brainchild of Ed Yost who became known as the ‘Father of Modern Hot-Air Ballooning’. Back in 1960 Ed hit on the idea of using propane gas instead of far more combustible hydrogen.

New York Times describes how he strapped himself into a deck chair, lit a propane burner to heat the air in the balloon, reached 500 feet and covered three miles. This reignited interest in recreational ballooning, a sport still popular as ever. But we digress. It’s time to fast forward to the main story in 1978 …

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AndersonAbruzzoNewman.jpg

Hot air balloon Double Eagle II successfully crossed the Irish coast on August 16, 1978. It headed for France where the captain, Larry Newman intended to hang glide to ground at Le Bourget Airfield near Paris, while the remaining crew flew on. However, they had to drop the hang glider as ballast over Ireland …

The crew decided it was too dangerous to land at Le Bourget Airfield. They crash-landed in a barley field 60 miles north of Paris after a 137-hour flight instead. Souvenir hunters stripped the wreck of logs and charts. However, the gondola survived and is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/mdl_photography/6991727635/

Three years on, two crew members of Double Eagle II (including the captain) recruited two new companions for a balloon flight from Japan to the United States across the Pacific Ocean. Double Eagle V took off from Nagashima, Japan on November 10, 1981, and landed in Mendocino National Forest in California 84 hours and 31 minutes later.

https://www.abqjournal.com/476850/balloonists-aim-to-shatter-records.html/two-eagles-balloon-flight-3

Or should we rather say crash land, because that’s what they did after a nearly 6,000-mile flight. In the process, they were weighed down by ice, and buffeted by a storm. However, this time the media gave them scant attention, because the world was agog with Space Shuttle Mission STS-2.

A concurrent Washington Post article described it as being like riding a roller coaster, ‘plunging hundreds of feet then rising again in the frigid air two miles up’. The crew jettisoned everything they had including tape recorders, cameras and even clothing to lighten the gondola.

‘For much of the journey, the ice-laden balloon would plunge from its 18,000-foot cruising altitude until warmer air melted the ice, then float up again, only to collect another heavy ice load,’ they told the Washington Post.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/sortingoutscience/4045587560/

The crew donned parachutes as they steered for Mendocino National Forest in the worst possible weather. Finally, they hit the side of a ridge and snagged the balloon in tall trees. They survived by detaching the gondola with a small explosive charge, and crashed down together in a heap of bodies. Quite miraculously they all survived, relatively unscathed.

New Airship Interest at Cardington Hangars, Bedford UK

UK company Aerospace Developments (London) Ltd began designing a non-rigid airship in the late 1970’s, It envisaged applications in civil and paramilitary roles, such as aerial advertising, promotional and pleasure flying, surveillance and maritime patrol duties.

Project Skyship 500 had a head start,in that it had access to the hangars at Cardington where ill-fated airship R101 took to the air in 1929.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cardington_Shed_BW.jpg

However, this time the engineers set tradition aside in favor of:

- Thin single-ply polyester, titanium dioxide dope-coated polyurethane, for the envelope

- A Kevlar nose-cone molded in the same manner as glass-reinforced plastic

- A gondola molded by Vickers–Slingsby from Kevlar-reinforced plastic

- Simplified controls. thrust vectoring fans driven by inboard-mounted Porsche engines

Aerospace Developments assembled the prototype Skyship 500 in 1979, although it only first flew the following year. It performed well, but suffered damage in a storm while tethered outside a hangar. The company pulled the plug on the project, and went into liquidation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Skyship500.png

Another company, Thermo-Skyships Ltd acquired the interest, and rebranded as Airship Industries. It went on to produce another 5 Skyship 500’s. These were used worldwide through to 1990, generally following the same original specification:

- Length 150 ft, diameter 34 ft, height 61 ft, volume 182,000 cu ft

- Crew 2, passengers 8, max gross lift 9,900 lb, max disposable load 2,780 lb

- 2 Porsche 930/01/AI/3 cylinder 204 hp horizontally-opposed, piston engines

- Max speed 58 mph, range 540 mi, endurance 12 hours, ceiling 9,770 ft

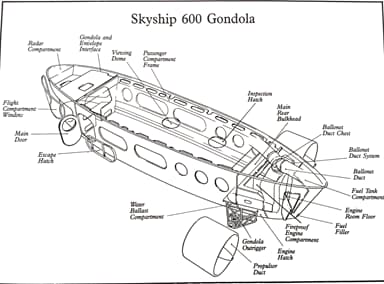

Skyship 500 was a successful design, although with hindsight it would benefit from a larger payload. This needed beefing up to maximum gross lift 13,400 pounds, and maximum disposable load 5,165 pounds. Engineers achieved this by extending the envelope by 30%, producing 50% more lift for the new Skyship 600.

https://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/ss600/index.html

Fresh attention was also given to gondola design, which now accommodated 12 passengers in greater comfort. The engineers stretched the gondola to achieve this, and added stylish round windows at the rear of the cabin.

Some 10 Skyship 600’s were built. A few were for military / industrial applications, although their main role was passenger services. Airship Industries offered scheduled pleasure flights over many capital cities of the world. They also became popular as stable camera platforms for recording major events.

https://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/ss600/images/SS600_Gondola_plan.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airship_Industries_Skyship_600#/media/File:GR_SK_Steigflug.jpg

Airships for Pleasure From Thunder and Colt

Actual dates are uncertain, but around this time hot air balloon company Thunder and Colt in Shropshire, England cottoned onto the idea of making a two-person blimp GA-42 for purposes of leisure and advertising. Their design complied with the following specifications.

- Length 60 ft, width 25 ft, volume 42,000 ft, lifting gas helium

- Lawnmower-size engine, speed 30 mph, climbing rate 1,000 ft / minute

The US Federal Aviation Agency and the UK Civil Aviation Authority both awarded Model GA-42 airworthy certificates. This made it stand out from the crowd of contemporary projects by ‘enthusiasts and dreamers’ according to The Independent newspaper.

https://www.shutterstock.com/editorial/image-editorial/aviation-airships-the-new-ga42-from-thunder-colt-ltd-1993-1358287a

By 1993 monthly operating costs for GA-42 had risen to £60,000 a month. According to The Independent ‘A good chunk of this money is spent on the pilot and the seven ground crew needed to bounce the blimp into flight and catch the mooring lines to bring it to a halt’.

Their reporter described the flying sensation as an unnerving experience. ‘The airship is caught between the maneuverability of a helicopter and the stability of a plane. It has the speed of neither. It is like a scary but exciting fairground attraction.’

https://www.trade-a-plane.com/search?make=THUNDER+%26+COLT+LTD&model_group=NO+MODEL+GROUP&model=COLT+AS-56&listing_id=2384906&s-type=aircraft

The U.S. Sentinel 5000/YEZ-2A BSAS Program

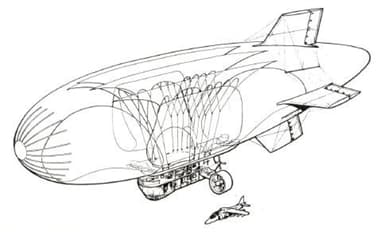

In 1985, the U.S Navy proposed a radar-carrying battle surveillance airship system (BSAS). Its request-for-proposals envisaged using airships as ‘airborne platforms’ to detect incoming hostile surface-skimming missiles.

The provisional design specification envisaged an aerial vehicle of approximately 2,500,000 cubic feet capacity. It should have endurance for two to three days, extendable to thirty days through refuelling and replenishment from surface ships. The Navy was reportedly interested in 40 to 50 airships if trials were successful.

Westinghouse Airship Industries Sentinel 5000

The U.S. Navy’s Battle Surveillance Airship System (BSAS) project underwent several name changes. These were in date order (a) Naval Airship Surveillance Program (NASP), (b) Organic Long Endurance Airborne Area Surveillance Airship System, and finally (c) Naval Airship Program.

Following several iterations the design specification evolved to:

- Length 469 ft, diameter 105 ft, 2,502,500 cu ft envelope with helium

- Two CRM Motor Marina diesel engines for regular operation

- Supplementary General Electric T700 turboprop for ‘dash’ situations

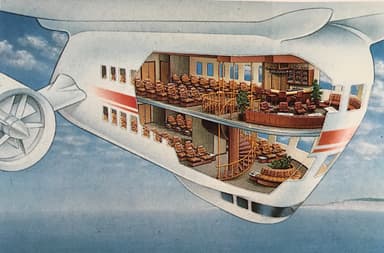

- 10 to 15 crew in a triple-decked, partly pressurised gondola

- A radar antenna mounted on the gondola but within the envelope

UK Airship Industries built a linear half-scale version it named Sentinel 1000. This had a larger envelope made of a new material that would eliminate routine in-hangar attention, and a ground-handling technique requiring a crew of just 8 assistants. Their work ended when the company went into financial difficulties in 1991, and Westinghouse assumed full control.

Airship Industries had also contemplated a civilian version of Sentinel 5000, accommodating between 140 and 300 passengers. It envisaged both luxury shuttle services ,and conventional scheduled flights. However, this interesting side line folded with the company.

https://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/Sentinel_5000/index.html

Westinghouse took over Airship Industries’ work, and successfully flew Sentinel 1000 in 1991. It proposed using this as a demonstrator platform for a future 5000 model, while also researching over-the-horizon targeting, and assisting with the drug disruption program.

The company researched fly-by-light optic fiber cables and introduced them in 1993. Sentinel 1000 became the first aircraft with fly-by-light controls to receive FAA certification. It may also have been the first aircraft to achieve this distinction.

https://www.airshipsonline.com/airships/Sentinel_1000/Index.htm

Plans were in place to fly a prototype Sentinel 5000 in 1998. However, an accidental fire destroyed the Weeksville hangar and its contents, including the sole Sentinel 1000 and the mock-up of the 5000’s gondola on August 2, 1995. Work continued until the Navy Airship Program canned the idea, and the project folded.

Record-Breaking Airships of the 1990’s

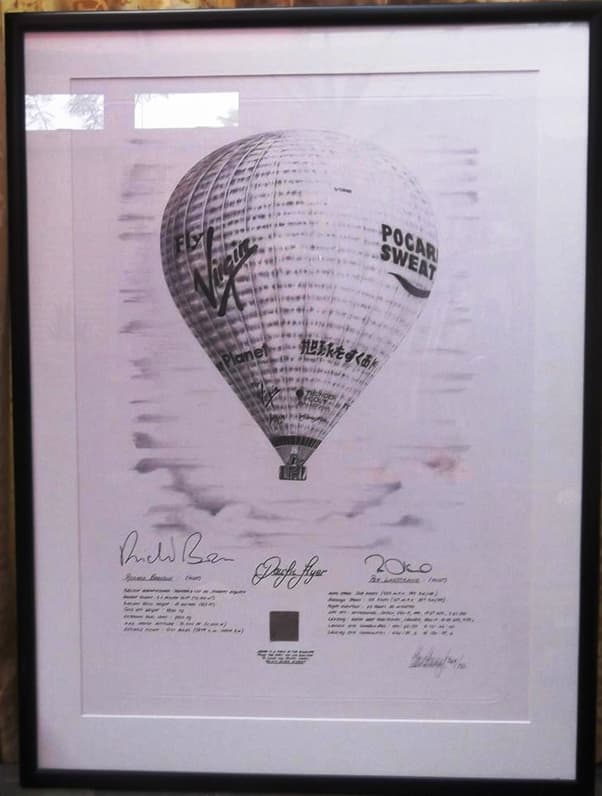

Swedish aeronautical engineer Per Lindstrand stands out in airship history in the final decade of the 20th century. He founded Lindstrand Balloons in 1991, and later Lindstrand Technologies Ltd.

That same year he completed the longest flight in lighter-than-air history, 6,761 miles from Japan to Northern Canada in company with entrepreneur Richard Branson. Their Virgin Pacific Flyer remains the largest hot air balloon in history.

https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/virgin-pacific-flyer-hot-air-balloon-1779517662

Per Lindstrand’s company built the world’s largest airship AS-300 for French botanists in 1993. This was a unique project for two reasons. In the first instance the capacity was 300,000 cubic feet. The second was its unusual application.

AS-3000 carried a large, underslung inflatable raft it was able to gently lower on top of rainforest canopies. This allowed botanists to access the treetops without causing significant damage to their subjects. The airship returned on request to collect them, or relocate them to another site.

http://www.hotairships.com/airships/lindstrand/as300/

Luftschiffbau Rises from the Ashes With Zeppelin NT

Count Ferdinand Von Zeppelin’s old company Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH re-emerged in 1993. Starter funds came from an endowment, which limited the use of funds to the field of airships. The value had grown down the years and was now quite a substantial sum.

The idea of re-establishing the company was first considered in 1988. By mid-1991 patents were in place, and market analysis suggested initial scope for around 80 sales of the Zeppelin NT new technology airship.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zeppelin_NT_in_Kalifornien.jpg

There was a public viewing of the prototype under construction in July 1996. In July the following year this completed a maiden flight of 40 minutes. However, the first full flight of 423 miles only took place in October 1999, following noise level measurements, avionic tests, and sundry take-offs and landings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeppelin_NT#/media/File:GR_NT_Heckpropeller.jpg

The final prototype was a departure from Zeppelin tradition in that the design was semi-rigid with internal triangular truss, and three longitudinal girders. Moreover, the envelope contained helium gas the company had finally managed to lay its hands on.

The primary specification was as follows:

- Length 246 ft, height 57 ft, diameter 46 ft, gross weight 23,6567 lb

- Crew 2, passengers 12 (or 4,188lb payload), volume 290,450 cu ft

- 3 × Textron Lycoming IO-360 air-cooled flat-four engines, 200 hp each

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lycoming_O-360#/media/File:LycomingIO360.JPG

This arrangement delivered a cruising speed of 71 mph, maximum speed of 77 mph, range of 559 miles, and service ceiling of 8,530 feet. The rear propeller arrangement ensured low-vibration flight suitable for environmental observation, troposphere research and natural resources prospecting.

Airship travel had completed its journey from dangerous and foolhardy, and was ready to enter the 21st century with renewed confidence. However, at this stage global warming and the need for greater carbon efficiency were not even on the horizon for many aeronautic engineers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeppelin_NT#/media/File:2003-07-26_18-54-50_Germany_Baden-W%C3%BCrttemberg_Hirschlatt.JPG