Our story begins on a day in 1801. When French military officer André Guillaume Resnier de Goué achieved a downhill glide of 985 feet, while waving wire wings covered over with waxed silky material, and breaking his leg when coming down to earth.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9_Guillaume_Resnier_de_Gou%C3%A9#/media/Fichier:Plaque_Resnier.jpg

Some thirty years later, French mathematician and brigadier general Isidore Didion remarked, ‘Aviation will be successful only if one finds an engine whose ratio with the weight of the device to be supported will be larger than current steam machines, or the strength developed by humans or most of the animals.’

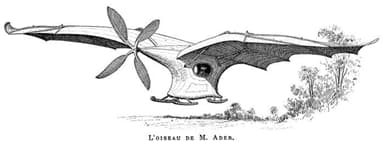

George Cayley Lays Down the Principles of Heavier than Air Flight

However, it was English engineer, inventor, and aviator George Cayley who earned the title of ‘father of the airplane’ in 1846, by clarifying the principles of heavier-than-air flight. This included defining the modern airplane in terms of fixed-wing, fuselage and tail assembly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Governableparachute.jpg

George Cayley published a design in 1852 for a manned glider or, as he called it a ‘governable parachute’ to detach from a balloon. However, he decided to launch a modified version from a hilltop in 1853.This device carried the first adult aviator across Brompton Dale near Scarborough.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Cayley#/media/File:George_Cayley_Glider_(Nigel_Coates).jpg

The Birth of Steam Power in the Air

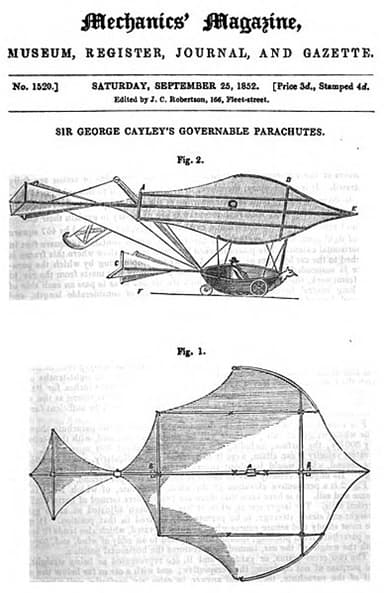

In 1842 William Henson of Nottingham, England designed, and patented an ‘aerial steam carriage’ monoplane with a wingspan of 150 feet and capable of carrying passengers.

He used a single pair of rectangular wings made of wooden spars covered with fabric, and braced internally and externally with wires. Propulsion would have been by steam had it flown, powering two contra-rotating six-bladed propellers mounted in the rear in a push-type system.

William Henson teamed up with John Stringfellow. His partner had a vision of an international aerial transit company, ferrying passengers to ‘exotic places like Egypt and China’, and this seized the attention of the media that published images like this.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Print_(BM_1871,0812.5370).jpg

The First Lighter-Than-Air Powered Flight (1848)

John Stringfellow went on to build a ten-foot wingspan, steam-powered monoplane in a disused factory in Chard, Somerset. This used two contra-rotating propellers pushing a maximum amount of air with low induced energy loss. It flew ten feet before becoming destabilized and suffering damage.

However, his second attempt was more successful after using a guidewire for launching. The repaired aircraft flew freely for 70 feet of straight, level, powered flight in 1848. A bronze model of it is on display outside the Chard Museum and there is more to see inside.

https://media-cdn.tripadvisor.com/media/photo-s/06/c3/1d/7e/chard-museum.jpg

https://www.tripadvisor.co.za/Attraction_Review-g667388-d2285612-Reviews-Chard_District_Museum_Heritage_Centre-Chard_Somerset_England.html

The Invention of the Aileron (1868)

There were many other gentleman scientists in England at the time greedily absorbing new discoveries that came flooding through. Of them, British scientist-philosopher and inventor Matthew Piers Watt Boulton deserves special mention. For he invented the aileron when he realized:

For the safety of an aerial vessel it is important to provide a controlling power not only to direct their horizontal and vertical course, but also to prevent their turning over by rotating on the longitudinal axis. A certain stability of the kind desired is afforded by using an extended surface whose sides make an angle from the axis upwards …

But it is desirable to provide a more powerful action preventing [rolling] rotation of the body in this direction. For this purpose a rudder of the following construction may be adopted:—Vanes or movable surfaces are attached to arms projecting from the vessel laterally or at right angles to its length.

When these vanes are not required to act they present their edges to the front, so as to offer little resistance to the vessel’s movement, but if the vessel should begin to rotate [roll] on the longitudinal axis the vanes are moved so as to take inclined positions …

Those on the ascending side of the vessel being caused to rotate to such an inclination that the air impinging upon them exerts a pressure downwards, while those on the descending side are so inclined that the air impinging upon them exerts a pressure upwards …

Thus the balance of the vessel is redressed and its further rotation prevented. The vanes may be moved by hand or by self-acting mechanism… (Patent application, 1868)

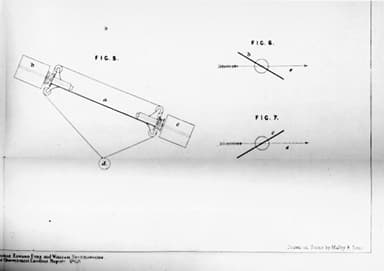

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boulton_aileron_patent,_No._392,_1868_-_Drawing_Figs._5-7.jpg

The First Monoplane Aircraft

French scientists were not keen to let their ‘old competitor’ England steal a march on them in the air. French naval officer, minor aristocrat, and inventor Félix du Temple de la Croix designed a monoplane with a tail plane, and retractable undercarriage.

He interpreted his ideas in a model first propelled by clockwork, and then by steam. Then he attempted a flight in a full-size prototype in 1874. It lifted off from a ramp under its own power, flew a short distance and glided to the ground, completing the first successful powered glide in history.

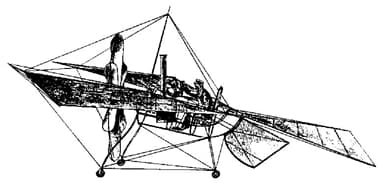

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1874DuTemple.jpg

The monoplane received propulsion from an ultra-compact steam engine, with high speed circulation and very small pipes packed together to obtain a high contact surface in the smallest possible volume.

An article in the Wall Street Journal of December 22, 2003 suggested ‘a guileless young sailor’ was at the controls on one of the flights, as a surrogate pilot. If this were the case, then that could have been the first powered, manned airplane flight. Perhaps beating the Wright Brothers by almost three decades but there is no conclusive evidence…

Towards Flight with Fuselage, Wings and Tail

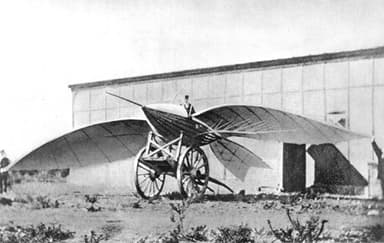

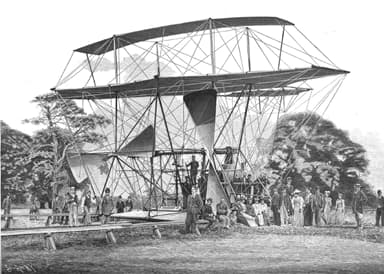

George Cayley’s ideas for the minimum requirements of heavier-than-air flight continued to take root. French aviator Jean Marie Le Bris built a glider based on those principles after detailed observations of birds. He towed it down a beach on a carriage pulled by a horse in 1856.

Anecdotal evidence suggests it rose 325 feet into the air during a 650 foot flight. If this was true, then it was the first winged flight that rose higher than the point of departure.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LeBris1868.jpg

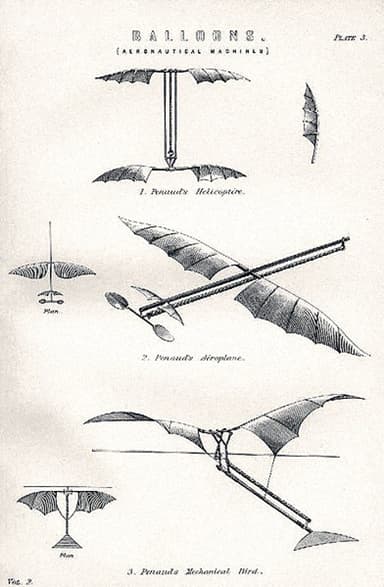

However, his compatriot Alphonse Pénaud came much closer to an aircraft that looked almost ‘modern’ when it flew in 1871. He had constructed successful models of aiplanes, helicopters and ornithopters with flapping wings previously.

However, his ‘planophore’ model was closer to George Cayley’s ideas, and incorporated a tail plane set higher than the wing line. This made an original, and important contribution to the theory of aeronautics

A model plane incorporating these features flew on rubber power for 130 feet in 1871. Alphonse Pénaud had grand plans for the future. But alas he could not garner support for his ideas. He took his own life in 1880 at the young age of 30 years.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:P%C3%A9naud%27s_flying_models.jpg

First Lift Off under Own Power

Things appear to have gone quiet on the airplane front after that for a while, arguably as the focus shifted to lighter-than-air flight in balloons and airships making more substantive progress.

Then French engineer Victor Tatin arrived on history’s stage in 1879. He created the first airplane that took off under its own power, after accelerating along the ground tethered to a pole.

Notable features included:

- Monoplane construction

- Wingspan 6 foot 3 inches

- Weight 4.0 pounds

- Propulsion compressed air

- Twin tractor propellers

- Separate horizontal tail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Victor_Tatin_aeroplane_1879.jpg

Birds and Bats and Steam Powered Flight

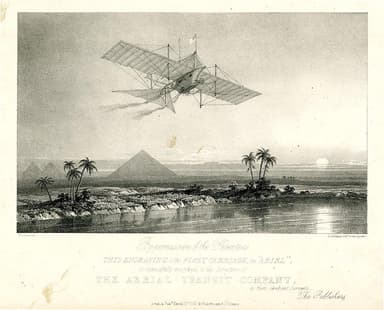

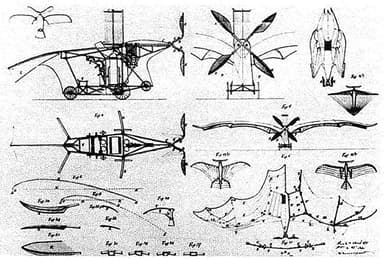

Clément Ader was an imaginative engineer and inventor who improved on Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone network. He also dabbled with stereophonic sound before applying his mind to V8 engines for the Paris-Madrid race.

However he is best known for his work on mechanical flight. In fact, he invested most of his time and money on a series of airplane projects beginning with his bat-like project, the Ader Éole.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:EolePatent.jpg

The specification of the Éole, which flew in 1880, was as follows:

- Propulsion: Bespoke 4-cylinder 20 hp steam engine driving a 4-blade propeller

- Wingspan 46 feet. Engine weight 112 lb, all-in weight 660 lb

Flight control was achieved by a combination of increasing or decreasing the wing area, flexing the outer portion of the wings up or down, and adjusting the difference between the curvature of the upper and lower surfaces of the wings.

The operator had to manage two foot pedals, six hand cranks, and the engine controls. Not surprisingly, its sole flight traversed 160 feet, 8 inches above the ground in what is best described as a powered take off, leading to an uncontrolled hop.

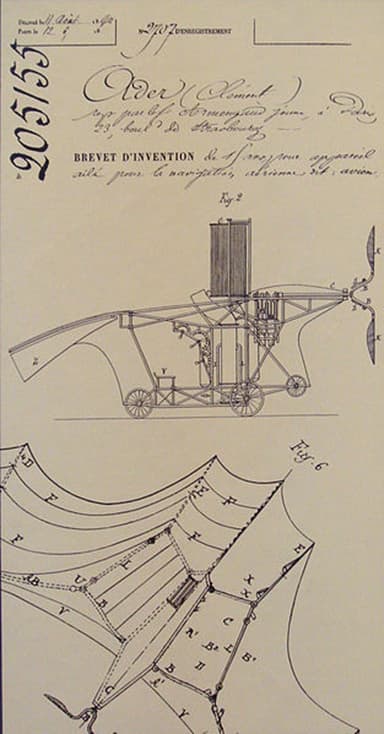

Adler tinkered with a second aircraft variously called Avion II, Zephyr or Éole II. He apparently never completed it, turning his attention to Avion III instead. Avion II, made from linen and wood hangs from the ceiling of Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris after extensive recovering and refurbishment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Clement_Ader_Avion_French_patent_205155_of_19_April_1890.jpg

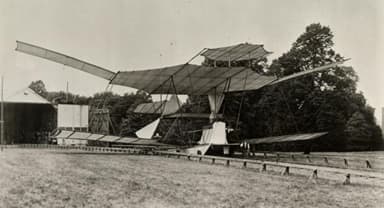

Avion III also resembled an enormous bat. However, it included 2 four-bladed propellers, each taking power from a 30 hp steam engine. Clément Ader completed taxiing trials on October 12, 1897. But a gust of wind caused it to slew off the track when attempting a lift off.

That was the end of the experiment for Adler. The French Army withdrew its support. He retired to write his book L’Aviation Militaire, which went through 10 editions and is notable for predicting maritime aircraft carriers.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Avion_III_20050711.jpg

The Challenge of the Power to Weight Ratio

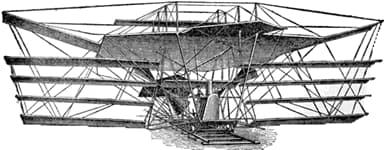

Sir Hiram Maxim was an American citizen who moved to the UK at age 41 after inventing the maxim machine gun and other innovative achievements. His father had previously sketched ideas for a helicopter, but was unable to find a sufficiently powerful engine to get airborne within weight limits.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maxim.gif

His son Hiiram dabbled with his father’s helicopter ideas, before deciding to build a fixed wing machine in 1889. He began with a series of experiments on aerofoil sections and propeller design, for which purpose he constructed a wind tunnel, and whirling test rig.

The specification for this ambitious project follows:

- Length 40 ft, wingspan 110 ft, weight 3.5 tons

- Two lightweight naptha-fired 360-horsepower (270 kW) steam engines

- Two 17-foot-diameter laminated pine propellers

- Four, wheeled outriggers restrained by wood rails outside a central track

- Rudders fore and aft to control vertical and lateral movement

Sightseers came from miles away to witness testing at 40 mph as described in colloquial accounts. It’s said the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, took a test ride accompanied by an admiral. Urban legend relates the prince was exhilarated by the experience, the admiral terrified.

http://www.kentscientists.org.uk/people/hiram-maxim.html

Disaster struck on July 31, 1894. The machine leaped forward after Hiram Maxim revved up the propellers and released the anchors. The aircraft rose off the track after a 250 foot run restrained by the mechanism. Then, after a further 1,000 feet the upthrust was too much for the restraining system.

Maxim found himself ‘floating in the air with the feeling of being in a boat’. He shut off the steam causing the machine to fall abruptly to the ground. Experiments ceased after that, when the inventor realized steam engines were not suitable for heavier-than air flight, in terms of their power-to-weight ratios.

http://aviation-history.com/early/maxim.htm

Review With the 20th Century At the Door

Some progress is made towards practical, heavier-than-air flight during this period. The fundamentals of fuselage, wings and tail are established. Ailerons provide lift and can influence the path of flight. The remaining problem is propulsion.

This is fundamental to achieving upward lift through forward movement. The problem is the engine. Steam adds too much weight. Batteries lack sufficient density. Internal combustion is in its infancy. But a second industrial revolution is well on track. Internal combustion will become the preferred form of propulsion.