The Challenge of Light Air Flight Continues in Dirigibles

An airship also commonly referred to as a dirigible differs from a balloon because it can be navigated in a chosen direction. In fact the name says it all because it derives from the Latin word ‘dingere’ meaning to direct.

Airships rise into their air because they are lighter than the atmosphere. They achieve this because their ‘stretched’ balloon contains a lighter-than-air lifting gas. This may be in a single volume or in a number of separate cells.

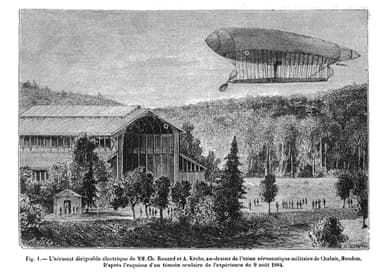

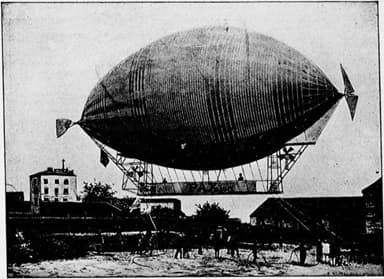

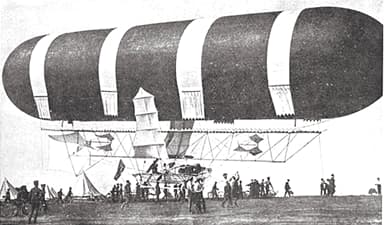

Airships have engines for motive power, and crew to direct them. They may also have payloads suspended beneath them. The first steerable airship that lived up to its name was the brainchild of Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs. Almost all airships since then have followed the same principles.

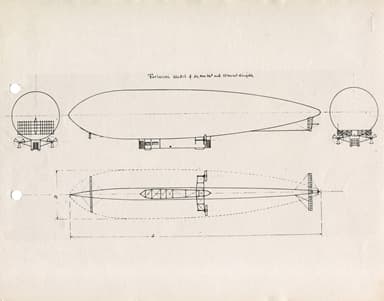

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_france_1884.png

Different Types of Airships Down the Ages

Airship design and construction have evolved in several directions since Renard and Krebs’ great achievement. Engineers have come up with unique terms to highlight the differences as we briefly explain below.

Aerostats

Aerostats rise up and remain aloft because they have buoyancy that makes them lighter than air. This distinguishes them from aerodynes (typically airplanes) that achieve lift by moving through air.

Dirigibles

Dirigibles are steerable aerostats. When Renard and Krebs called their La France a dirigible they were using the French word ‘dirigeable’ meaning navigable in a chosen direction.’

https://www.quora.com/Is-a-blimp-basically-an-airship

Blimps

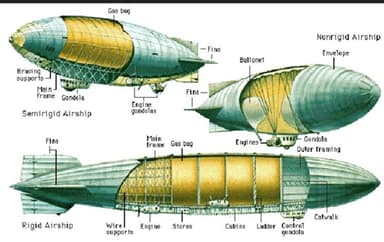

The La France aerostat was a balloon filled with lighter than air gas. It obtained its shape from the dimensions of the balloon without any supporting frame inside. Airships of this type have been called Blimps since the First World War.

Semi-Rigid Airships

Semi-Rigid Airships are a hybrid compromise between ‘Zeppelins’ and ‘Blimps’. They (usually) have keels along the bottom to prevent the generally unsupported envelope distorting owing to heavy payloads.

Zeppelins

Rigid airships have a framework to support the balloon enclosure, and provide a structure for placing smaller bags inside. This class of aerostat takes its name from the German Zeppelin company that produced the first rigid airships.

From 1884 to the Turn of the Century

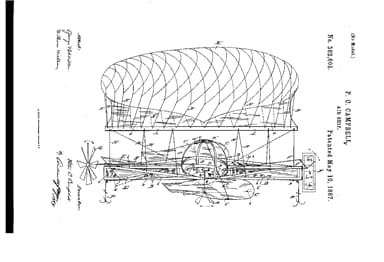

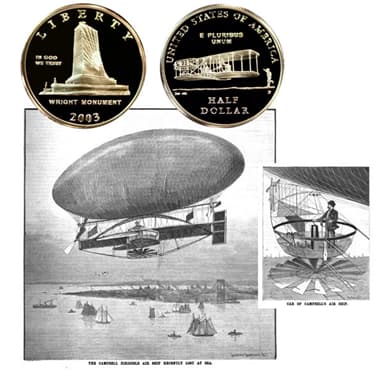

A Peter C. Campbell registered a U.S. patent for the ‘Campbell Air Ship’ four years after Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs made their historic flight. The Campbell airship was reportedly lost at sea, for the rest it largely remains a mystery.

https://patents.google.com/patent/US362605

The Chicago Tribune of January 8, 1891 reported their airship was capable of lifting an auto while moving upward, downward and laterally. It was a ‘cigar-shaped balloon’ 15.5 feet long and 5.5 feet high with an ‘iron car’. Propulsion was by ‘huge propellers’ and two wings ‘used for a parachute.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/35863110/chicago-tribune-8-jan-1891-p-12/

http://atlcoin.com/atlcoinblog/2018/07/16/expected-to-practically-navigate-the-air-first-flight-commemorative-half-dollar-coin/first-flight-half-campbell-air-ship-1889-w/

German publisher and amateur aviator Friedrich Wölfert threw his hat in the ring in 1887, when he built the first of three petrol-powered airships. He chose Gottlieb Daimler’s new petrol engine for propulsion during flights.

The so-called grandfather clock motor completed a six-mile flight from Cannstatt to Aldingen. Demonstration trips followed in Cannstatt, Ulm, Augsburg, Munich, and Vienna. Then in 1896 one of Wölfert’s airships ascended to 6,360 feet, a new record height.

Alas, disaster struck the intrepid aviator during a demonstration flight at Tempelhof attended by guests from Japan, China and Greece. The eight-horsepower Daimler petrol motor caught alight in December, 1897. The craft he had named Deutschland plummeted 670 feet to the ground killing Friedrich Wölfert and his mechanic instantly.

http://carwp.blogspot.com/2013/08/1888-1897-wolfert-daimler-airship-600.html

Hungarian David Schwartz born 1850 was the son of a timber merchant but had no technical training. He became excited by the idea of building his own airship while he was still a young man, and decided to clad the gas chamber with the new-fangled metal, aluminum.

His first airship failed to achieve sufficient lift in 1896, because of the low-quality hydrogen gas he procured. His second, 56-foot long one was more ambitious, with a 16hp Daimler petrol engine driving four propellers. The envelope was fabricated from 0.2mm aluminum sheets.

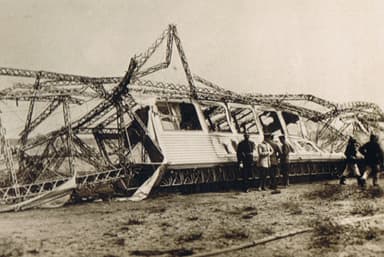

David Schwartz was away on business in Vienna when his zeppelin filled with gas for the first flight on November 3, 1897. The excitement proved too much for him. He collapsed, and died shortly afterwards. Back in Berlin the airship broke free from the tethering ropes as mechanic Ernst Jägels climbed aboard.

Jägels was unable to regain control after the drive belt slipped off the left propeller. The right one also failed at an altitude of 1,670 feet. But he was able to open the newly fitted gas release valve and land safely. However, the airship rolled over and collapsed, damaging it beyond repair.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SchwarzAirship.jpg

Medical doctor and inventor Konstantin Danilewsky built four human-powered dirigibles in what is now Ukraine between 1897 and 1899. They had gas volumes between 5,300 and 6,400 cubic feet, and completed around 200 experimental flights without any serious incidents recorded.

“When I was still a student, I frequently thought that it would be very simple and easy to arrange a flying apparatus so that at the command of the aeronaut (he could) ascend into the air, descend, or stop and motionless in the air and generally maneuver; and all this can be done as many times as necessary without discarding any ballast and without releasing the (lifting) gas.

To do this, you just need to lighten the weight of a person with a hydrogen balloon; but not completely – rather to leave some of its weight with an unbalanced balloon, and now the man himself will raise the remaining weight by his work on his wings: when he works, the apparatus rises into the air; will he ceases to work – it will lower.” (Konstantin Danilewsky)

https://welweb.org/ThenandNow/Danilewsky.html

A New Century Builds Unstoppably to World War 1

German Count Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin, born 1838 strides the stage of early aviation like a colossus. He joined the army after a private education and was a lieutenant by age 20. Then the army gave him leave to study science, engineering, and chemistry.

He travelled toNorth America in 1863 to act as an observer during the Civil War. After that, he explored the upper reaches of the Mississippi river in the company of Indian guides.

He encountered German-born itinerant balloonist John Steiner in Saint Paul at the confluence of the Minnesota River in 1863. There, he made his first aerial ascent that was to inspire his dream of building a lighter than air dirigible. Then he returned to the army for two decades where he commanded several brigades as general.

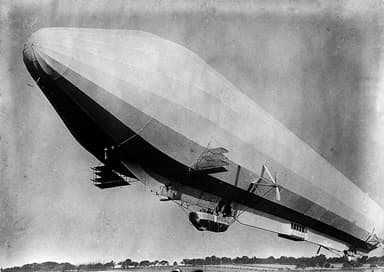

But Ferdinand could not let the thought go of a rigid aluminum frame covered over with a fabric envelope containing separate multiple gas cells. He imagined a gondola beneath with an engineer at its controls. He hired engineer Theodor Kober to do the design work which he patented. Then on July 2, 1900 his brainchild LZ1 rose majestically into the sky above Lake Constance.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:First_Zeppelin_ascent.jpg

The 420-foot rigid dirigible had a diameter of 38 feet and a useful lift of 27,400 pounds. Twin Daimler 4-cylinder water-cooled piston engines with power outputs of 14.2hp achieved 17mph under favorable conditions.

Pitch control was by a 220lb weight attached beneath the hull, and winched fore-and-aft to maintain the correct attitude. Two 20-foot long aluminum gondolas suspended on a metal frame below, one for the crew and one for the passengers.

Five people were on board Zeppelin airship LZ1 on her maiden flight. They rose to 1,350 feet and travelled for 3.71 miles before encountering technical difficulties. One engine had failed, and the movable weight was stuck in one position. The airship suffered damage during an emergency landing.

LZ1 flew twice after that, once on October 17, and once on October 24, 2020. The giant dirigible showed its potential by exceeding La France’s speed record. But investors were not convinced and the project had run out of money. The Count dismantled the giant craft, sold the scrap and tools, and liquidated the company. But the memories and challenges lived on.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeppelin_LZ_1#/media/File:Daimler_NL_1-Zeppelinmotor.JPG

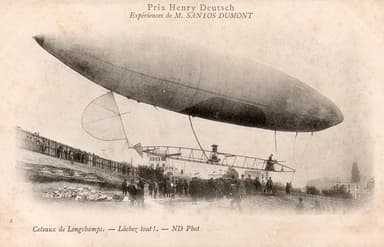

Meanwhile, Brazilian inventor and aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont was experimenting with balloons and dirigibles. He was the scion of a family of coffee producers and this provided a steady stream of funding. His particular interest was solving the problem of steering balloons.

The success of La France directed his interests to dirigibles. The Deutsch de la Meurthe prize was up for grabs, and Santos-Dumont has it in his sights. The criteria were as follows

1… Fly from Saint-Cloud Park near Paris to the Eiffel Tower 2 miles away and back again in 30 minutes

2… Maintain an average ground speed of at least 14 mph which was necessary to meet that requirement

Alberto decided to construct a special airship for the competition that was open from May 1, 1900, to October 1, 1903. His Santos-Dumont No.6 dirigible was 108-feet long, and achieved 25mph thanks to a 12hp Buchet 4 cylinder inline water-cooled piston engine.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santos-Dumont_number_6#/media/File:Santos-Dumont_dirigeable_1901.jpg

Notable design features included a single maneuvering valve, and two automatic pressure-relief valves. There were also two ripping panels to allow rapid venting in an emergency.

The Santos-Dumont No.6 dirigible earned the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize on October 19, 1901 when it completed the round trip in 29 minutes, 30 seconds. However, the airship met with an accident when the balloon tore open over water on February 14, 1902.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Acidente_de_Santos_Dumont_com_o_Dirig%C3%ADvel_n._6.jpg

Alberto Santos-Dumont developed airship No 7 with a view to competing for the lucrative prize at the 2004 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The objective was to:

- Make three 15 mile flights at an average speed of 20 mph

- Land undamaged not more than 150 feet from the starting point

Alberto Santos-Dumont was well received on account of his fame, and was invited to White House to meet President Roosevelt. However, he found the balloon fabric ripped as if by a knife when he returned to assemble No 7 shipped in crates.

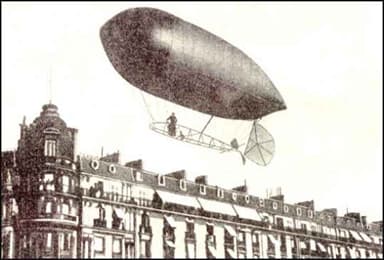

He built airships No 8 and No 9 before he decided to turn to heavier-than-aircraft where he believed the future lay. However, it would be many years before Parisians ceased remembering his airships flying over their rooftops.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alberto_Santos-Dumont#/media/File:Santos_Dumont_No.9_Paris.jpg

Perhaps as a consequence interest in dirigibles spread throughout Europe. Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo came up with an innovative design with a non-rigid body, but with internal bracing wires. His cross-over thinking overcame flaws associated with both rigid and balloon type airships, providing greater flexibility, more passengers, and larger payloads.

Quevedo sold his intellectual property outside Spanish territory to French company Astra-Torres who carried his ideas forward during the First Great War. There were many other minor heroes during this innovative period before regulations began to stifle some of the brightest ideas that lacked financial backing. However, there were some remarkable exceptions, a few as always ended in tragedy …

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Catastrophe_of_the_Balloon_%22Le_Pax%22#/media/File:Le_ballon_dirigeable_Pax.jpeg

Thomas Scott Baldwin was a pioneer balloonist who later developed a fixed wing aircraft, the Red Devil. He created a small pedal powered airship in 1900 but this remained a curiosity. Then in 1904 he created the airship ‘California Devil’. This earned him the informal title ‘Father of the American Dirigible’.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:California_Arrow-01.jpg

A 7 hp Curtis Hercules motorcycle engine powered the aerodynamic, cigar-shaped hydrogen-filled dirigible. The pilot, John Beachey, an aviator and barnstormer completed the first controlled circular flight in America on August 3, 1904 at Idora Park, Oakland California. Another pilot, Roy Knabenshue made exhibition flights at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri later that year.

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/usa-baldwin-thomas-california-arrow-lighter-air-lta-airships-photograph

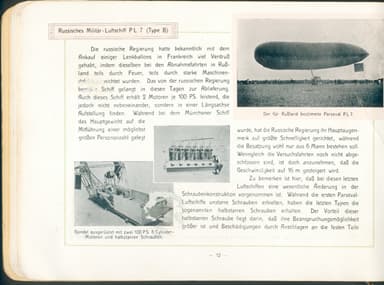

Russia began purchasing airships from France and Germany in the first decade of the 20th century. It ordered several non-rigid / semi-rigid ones from German aircraft manufacturer Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft in the years leading up to World War 1.

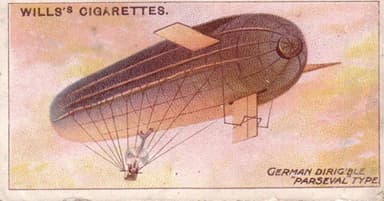

One, by way of an example, was Parseval PL-7 Grif (Type B) from German aircraft manufacturer Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft. The specification was:

- Length 236 feet, diameter 46 feet, volume 235,000 cubic feet

- Maximum speed 31 mph, flight duration 20+ hours, ceiling 8,200 feet

- Crew 3 / 4, crew and passengers 12 / 16

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_and_Russian_airships#/media/File:Parseval-Broschuere-12.png

Other airship designers, builders and aviators were active at this time in the evolution of flight. Those deserving special mention in the period leading up to 1914 include:

- French company Lebaudy Frères specializing in semi-rigid airships from 1902

- German firm Schütte-Lanz building the wooden-framed SL from 1911

- Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft making the Parseval-Luftschiff series from 1909

Meanwhile Count von Zeppelin was determined to continue pursuing his vision of practical air transport. He followed up with a revised version, LZ2 that first flew in 1906. This used triangular, not flat girders for greater structural strength, and deployed elevators to control pitch instead of the lead weight.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LZ_2_Flug_1905.jpg

Power for the 414-foot-long LZ2, which only flew twice, was provided by two 84hp Daimler piston engines. These were able to achieve a top speed of 25mph with a range of 680 miles, and a service ceiling of 2,800 feet.

The potential of dirigibles did not escape the attention of other military strategists either, in the decade building up to World War 1. Astute generals greedily grasped the idea of being able to view the opposing side from above, and direct artillery fire over Morse code.

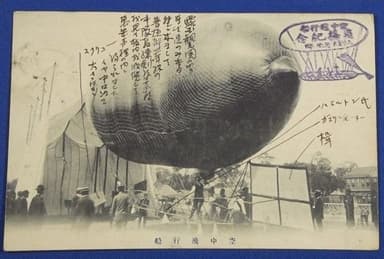

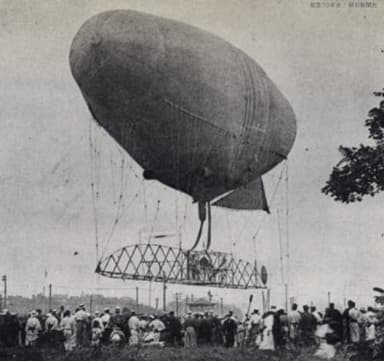

The earliest report of an airship in Japan relates to a demonstration model some 60 feet long. An Englishman named Hamilton demonstrated it in Tokyo Park, probably in the first decade of the 19th Century. Hydrogen capacity was 8,000 cu ft. Propulsion came from a small petrol engine mounted in the centre of the suspended gondola, driving a tractor propeller.

https://www.pinterest.jp/pin/196117758758984905/

Interest Shifts from Competitions to War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nulli_Secundus.jpg

The potential of dirigibles did not escape the attention of military strategists in the decade building up to World War 1. Astute generals grasped the idea of being able to view the opposing side from above, and direct artillery fire over Morse code.

The United Kingdom built its first military dirigible Nulli Secundus No 1 at Farnborough. The 122-foot airship had a cylindrical envelope constructed from membranes of ox intestines unmatched for their resistance to tearing.

Steering was by a rudder and elevators at the rear, a pair of large elevators amidships and a further pair at the front attached to a long, triangular section hanging beneath the elongated balloon. A small gondola hung beneath this contraption housing the crew and the propulsion source.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nulli_Secundus.jpg

Power came from a 50 hp Antoinette light petrol engine driving a pair of two-bladed aluminum propellers via leather belts. However, the propeller pitch could only be adjusted when the dirigible was on the ground with the motor stationery.

The Nulli Secundus, translated second-to-none, had a checkered history. Her early flights suffered from engine failure and inability to withstand strong headwinds. She was deflated and partially dismantled after several guy ropes broke free while tethered. However, the dream would live on a little longer.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoinette_(manufacturer)#/media/File:Antoinette_8V_front_cropped_Museo_scienza_e_tecnologia_Milano.jpg

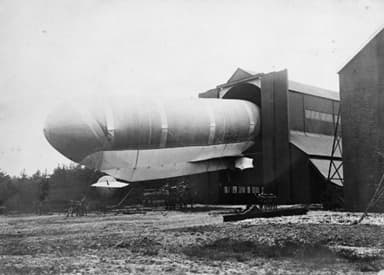

The British military authority rebuilt the salvaged remains into Nulli Secundus II with several improvements. These included a silk outer skin, a modified understructure, improved control surfaces, a new drive train, and a ground spike.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nulli_Secundus_II_emerging_from_shed_IWM_RAE-O_698.jpg

However, Nulli Secundus only made two flights. The first was a demonstration for dignitaries. The second was a training mission for navy personnel. They scrapped the project after that, presumably due to lack of investor interest.

But the Antoinette light petrol engine lived on to power Cody 1. This was the biplane that made the first recognized, powered and sustained flight in the United Kingdom on 16 October 1908.

Japan established a balloon unit in Tokyo in 1907, following some successes during the 1904 Russo-Japanese War. It then formed the Provisional Military Balloon Research Association (PMBRA) two years later.

The organization’s brief was to investigate all forms of manned flight. There were representatives from the Army, Navy, Tokyo University and Central Meteorological Observatory on the panel.

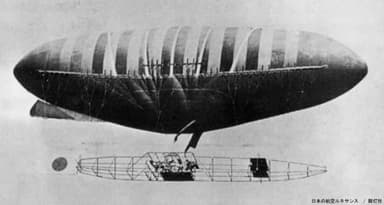

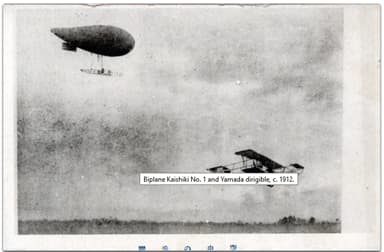

Its first project was Yamada-shiki No.1, meaning Yamada Type 1. The non-rigid project had 56,000 cu ft hydrogen capacity, and was 60 ft long. There was a rudder at the stern, and a small elevator between the platform and the bow. A 12 hp auto engine drove the pusher propeller.

She completed a round trip between Yokosuka to Osaka in September 1910. Unfortunately that is all the information on record about it.

https://av8rblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/11/historical-look-at-japans-first-dirigibles/

Please obtain permission to use

Meanwhile Count von Zeppelin was perfecting his vision of a military dirigible. It’s time would come when it terrified London.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zeppelin-lz3-intheair-1909.jpg

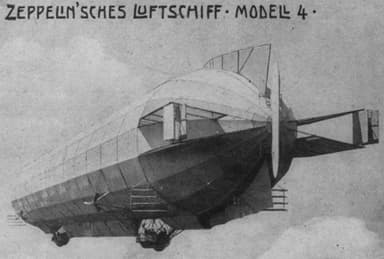

Count von Zeppelin’s new model LZ3 used the same hull, engines and propellers as LZ2. However, it benefited from two pairs of biplane elevators to counter LZ2’s severe pitch instability.

One set of these elevators was in front of the forward gondola, and the second behind the rear one. There were also fixed biplane horizontal stabilizers at the rear of the hull.

The influential passengers who flew on that trial – including the German Crown Prince – must have been impressed by the improvements, because the German army purchased the giant dirigible. They ordered a second one, LZ4. This flew once until a strong wind broke the moorings and destroyed it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LZ_4#/media/File:Zeppelin_airship,_model_4,_with_inset_bust_portrait_of_Graf_Zeppelin_LCCN2002722155_(cropped).jpg

The drums of war were beating loudly in Italy too, where Italian pioneer Enrico Forlanini finally launched his Leonardo da Vinci in 1909 after first sketching his ideas in the year 1900.

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/lta-airships-italy-forlanini-enrico-f1-leonardo-da-vinci-photograph

The Leonardo was 130 feet long, and with a maximum speed of 32 mph using a single, 40 hp Antionette engine. Enrico continued building airships after the war broke out, and was still hard at work when he died in 1930.

Forlanini airships were advanced for their day. Their gondolas had three separate compartments, one for the command cabin, one for the passenger cabin, and the third for the machine room. But across the Atlantic others had even more ambitious ideas.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Signal_Corps_Dirigible_No_1_afmil-01.jpg

Pioneer balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin designed and built what was arguably America’s first dirigible in 1904. Chief Signal Officer Brigadier General James Allen urged the U.S. army to purchase it, in the light of military applications in Europe.

The first known military flight was on May 26, 1908 at Fort Omaha where pilot Lieutenant Lahm and Lieutenant Foulois were able to maneuver SC-1 at will. However, the airship never flew again. It was scrapped in 1912. The U.S. Army did not purchase another dirigible until after World War I. However, things were happening in northern Norway.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wellman_air_ship_LOC_ggbain.03344.jpg

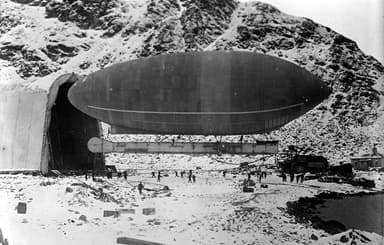

American explorer Walter Wellman developed the idea of flying a dirigible to the North Pole after he failed to reach it by boat and sledge in 1894. However, it was several decades before airship technology caught up. His first attempt at flight at Spitsbergen, northern Norway in 1906 failed after the engines fell apart.

However, Walter Wellman could not take defeat sitting down. He returned to Spitzbergen in 1907 with a larger, 185-foot hydrogen airship without airframes, but with three internal-combustion engines. These delivered a total 80hp energy to two propellers, one fore and one aft. However, this effort also crashed after a few miles due to bad weather.

Undeterred, the intrepid explorer made a third, final attempt in July 1909 which traversed 40 miles before the ‘equilibrator’ altitude-control device failed, and it ascended rapidly to 5,000 feet, before venting hydrogen and descending to the ground. The American explorer abandoned the project after Dr Frederick Cook claimed to have reached the pole.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Walter_Wellman%27s_America.png

On October 15, 1910 Walter Wellman attempted the first North Atlantic crossing from Atlantic City. His ‘America’ benefited from a spark-gap radio set and made some of the earliest air-to-ground transmissions. However, the engines failed after passing through a storm and they descended and began floating approximately south.

They made one of the earliest radio distress signals. The Royal Mailship Trent spotted them after they covered a total 1,370 miles from their launch site. Walter Wellman deflated the balloon after opening the hydrogen gas valves. All passengers survived using the lifeboat, including mascot cat Kiddo. However, the airship was never seen again.

The Japanese army ordered a larger version of Yamada-shiki No.1 in 1911. Fujikura Industrial Company would fabricate the envelope for Yamada-shiki No.2, to carry a gondola built by Mitsubishi.

No 2 was longer than No 1 at approximately 100 ft. She had a 50 hp, four-cylinder water-cooled engine at the center of the open gondola made of tubes in a triangular cross section. Apparently she made a first successful flight before being irreparably damaged in an incident for which there are various explanations.

https://av8rblog.wordpress.com/2017/04/11/historical-look-at-japans-first-dirigibles/

We don’t know much at all about Yamada-shiki No.3 reputed to have first flown in 1911. It may have been a resuscitated version of No 2. One source suggests Japan sold the airship to China after it completed a 625 mile flight from Osaka to Tokyo and back.

Yamada-shiki No. 4 followed in 1912 / 1913. Again details are thin, although it’s possible it was also sold to China where a hangar fire destroyed it during a storm.

At the end of the Yamada-shiki period, Japan’s Provisional Military Balloon Research Association (PMBRA) decided to come up with a different airship design. They designated it Kai-shiki I-go meaning Association Type.

The Birth of Commercial Flight

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin established the aircraft manufacturing company Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH in 1908. ‘Luftschiffbau’ means the building of airships, and this is exactly what he intended to do. His company quickly became the leading manufacturer of military and civilian lighter-than-air aircraft.

However, the uptake of orders from the German military was slow. And so Zeppelin founded the “Deutsche Luftschifffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft” (DELAG) in 1909 to take up his manufacturing slack.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LZ7_passenger_zeppelin_mod.jpg

The company’s flagship was Zeppelin LZ 7 which it named Deutschland. A cruising speed of 32 mph made it unsuitable for intercity flights. And so the company used it for local pleasure trips until a heavy storm brought it down on June 28, 1910.

The second zeppelin, LZ 6 was pressed into service after the army declined to purchase it. There were daily flights starting late August until a hangar fire destroyed it on September 14.

The insurance paid out. DELAG ordered its replacement LZ 8 Deutschland. This lasted a few weeks until it broke its back in a storm. However, the company’s luck was about to turn.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zeppelin-Luftschiff_Schwaben.jpg

Schwaben is a region in southwest Germany. Its namesake 460-foot dirigible had three 145 hp engines delivering a top speed of 47 mph. The hull was wider in the middle, to accommodate 20 people in a passenger cabin amidships commanding spectacular views.

The forward gondola housed the control position and one engine, while the second housed the other two engines to the rear.

Schwaben carried 1,553 passengers successfully. It also completed long-distance flights from Baden Baden to Frankfurt, Düsseldorf and eventually to Berlin. However, she too fell victim to a hangar fire on June 18, 1912.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LZ_10_Schwaben_Ausgebrannt_1912.jpg

By July 1914, Deutsche Luftschifffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft had transported 34,028 passengers on 1,588 commercial flights. Its fleet had travelled over 107,000 miles in 3,176 hours flying time. Its small fleet was growing, but war was declared the following month.

Airships LZ 11, LZ 13, and LZ 17 were all pressed into service for the German Army. The innocent age of flight was over. The world would probably never be the same again.

Military Development Continues

The Italian military used airships to bomb their enemy during the Italo-Turkish war of 1911 to 1912. It built approximately 20 M-Class semi-rigid vessels carrying bombs weighing 1000 pounds it used for attacking and anti-shipping missions.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Zeplin_orta.jpg

Japan’s airship development company PMBRA once again placed orders with Fujikura Industrial Company for the envelope and Mitsubishi for the gondola. Kai-shiki I-go No 1 was longer than Yamada-shiki No. 2 at 159 feet with hydrogen capacity 103,500 cu ft.

The central gondola had a square tubular cross section, and housed three crew in the rear with side panel protection. A Wolseley 60hp four cylinder in-line water-cooled petrol engine driving a tractor propeller was up front. There was a dorsal rudder at the rear of the envelope, and rudder above the forward section of the gondola.

https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/attachments/i-go-airship-jpg.525779/

Kai-shiki I-go No 1 first flew on October 25, 1911, and covered 3 miles in 10 minutes at an altitude of 132 feet. Information on other flights is scant, although it achieved a maximum endurance of 5 hours before dismantling in 1914.

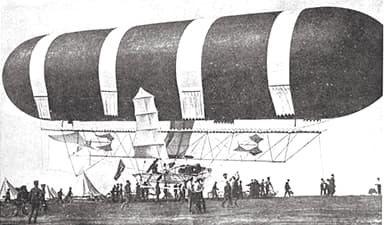

The Provisional Military Balloon Research Association also ordered an airship from Germany in 1911. This was the non-rigid Parseval PI-13 built by Deutsche-Luftfahrzeug-Gesellschaft works near Berlin.

The airship was 252 feet long, with a 50 ft diameter and 310,950 cu ft capacity. Two Maybach 150hp six cylinder in-line water-cooled petrol engines drove four-bladed pusher propellers on either side of the gondola rear. Flight controls included horizontal stabilizers, a large dorsal rudder, and a small ventral fin to the envelope rear.

https://av8rblog.wordpress.com/2013/10/19/15-german-parseval-type/

This took Japanese airship technology to a new level. A team of officers went to Germany to observe construction, and receive training in operating the vessel. A German engineer accompanied them to Japan, to supervise assembly and construction of a suitable hangar.

The airship flew for the first time on August 31, 1912 with a mixed crew. Thereafter it offered popular sight-seeing trips before colliding with a monument to a Japanese emperor in November 1913.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Parseval_Versuchsluftschiff.jpg

The Japanese Army repaired Parseval PI-13 in 1914, and modified it justifying the new name Yuhi-go (Majestic Flight). Modifications included:

- Enlarging the envelope

- Replacing the fabric

- Lengthening the elevator

- Rebuilding the gondola

Length was now 279 ft, with hydrogen capacity increased to 353,360 cu ft. The vessel was 220 pounds heavier, but the engines were the same. Majestic Flight took off on April 21, 1915. Several longer flights followed, with engine reliability an increasing problem.

Spares were unavailable because the two nations were on opposing sides in World War I. The Japanese Army lost interest in airships in favor of fixed wing aircraft. They scrapped Majestic Flight in 1918. This had been coming for a while.

http://www.oldtokyo.com/kaishiki-no-1-biplane-yamada-dirigible-c-1911/